Event Details

Location: Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh

Venue: Eco-Centre of the Forest Department

Date: Aug 24-25

Attendees: Roughly 70; district- and block-level officials, field staff of the forest dept., village representatives from panchayat

We have just held a very successful workshop on the Forest Rights Act (FRA) in the Sheopur district of Madhya Pradesh.

Sheopur is about 400 km south west of Delhi, on the border of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. The Sheopur district was created in 1999, by separating it from the Morena district. In 2006, Sheopur was among the 250 most backward districts in India. The district covers about 6,600 sq km, and over 60% of the land area is classified as forest. The district contains the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary, with a total area of 345 sq km, of which about 31 sq km is revenue land.

The district has some of the poorest communities in the country including a large tribal population. It is home to the Sahariya tribe, which is classified as a Primitive Tribal Group and is one of the most backward tribal groups in India. The 2011 Census puts the population at 687,000, and 84% of the people live in the 587 villages. The tribal population is estimated at 140,000, about 21% of the total, and 98% of whom belong to the Sahariya tribe.

A section of audience at the Sheopur workshop, which included senior district officials, field staff, and village representatives.

So far, about 6,700 claims have been filed by people under the Forest Rights Act, in Sheopur district, of which only 2,200 claims have been approved, which includes individual family claims, and 196 community forest rights claims. However, on the basis of the population data, there could be over 25,000 individual claimants in the Sheopur district.

Technology Diffusing Conflict in Rural India

From Left to Right: Prof Jitendra Shah, IIT Bombay, Barun Mitra, Liberty Institute, D.B. Patil, District Collector Sheopur, Divisional Forest Officer, Ambrish and Trupti Mehta (ARCH).

This led to loud commotion from the audience. There were vigorous claims, counter claims, and accusations of misuse of the law by participants from the forest department and the communities. With many claims having been rejected, the people felt that the system was unjust.

This laid the ground, for Ambrish to demonstrate the advantage of using satellite images freely available on Google Earth. Barun Mitra moderated the discussion, and discussed how a transparent system could help diffuse the sense of conflict between the community and the officials.

We gave a small demonstration of how a plot of land could be mapped, and then showed how that plot looks in a satellite image from Google Earth. People could see the nature of land in the imagery of 2013, as well as 2010 and 2006.

As the discussion progressed, and we showed them how the satellite images showed the status of the land in 2013, as well as in earlier years, particularly around 2005, which is the legal cut-off. Most participants were surprised at the ease with which they could themselves assess the status of the land, that is whether the land was under cultivation at the cut-off date of December 2005, or not.

Barun Mitra, the local tehasildar, in charge of land records, and Trupti Mehta during a visit to the small hamlet of Hanumankheda.

Trupti Mehta of ARCH, actively engaged with community leaders and village level officials discussing the details of the current process under the FRA being adopted, and the possible ways of improving it, by adopting our methodology.

Prof Jitendra Shah, of IIT Bombay—who has been working towards various participative use of GIS—compared various technologies that could encourage ordinary people to use GIS more actively to improve governance. He showed how apart from hand held GPS instruments that Android based smart phones could also make GIS and satellite images more easily accessible to people.

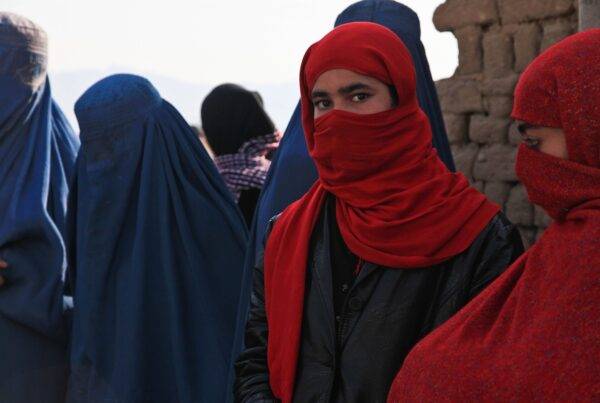

A section of the people from the hamlet of Hanumankheda, in Sheopur district.

1) Lack of any supporting evidence demonstrating that the family indeed had possession and was farming the plot of land as of December 2005.

2) The inability of non-tribal communities living in forest areas to show that they have been resident of the area for 75 years, as stipulated by the current law.

There was a general agreement on the significance of satellite imageries of around 2005 in solving the former problem. Whereas village land records, especially previous mutation entries, together with earlier voters’ list could be useful for resolving the latter problem.

NEXT STEPS:

With the help of the district administration, we are now planning a pilot programme in that area to demonstrate, sensitise, and train the local staff as well as the community. We will assist in the assessment of the land claims in each village, and use the satellite imagery to determine a list of priority villages where the claims seem genuine. This may help resolve much of the land claims that have so far been rejected due to a lack of supporting evidence.

The forest department too would like us to undertake our GPS based land mapping in three representative forest villages, one in each of the blocks in the district. The objective is to expose the field staff of the forest department, as well as the communities, to the actual process of mapping and documenting land claims. This would also give an idea of whether our methodology could be successfully deployed in the Sheopur district.

This workshop has been very rewarding as it was our first opportunity to demonstrate the utility of our system to a team of senior district level officials. And particularly, it was very encouraging to see how officials from the forest department and the local communities both looked at the prospect of settling their conflicting claims in a more amenable manner.

We sincerely appreciate the initiative taken by the district collector, Shri DB Patil, for inviting us, and giving us an opportunity to learn about the actual situation and issues on the ground in Sheopur. We are looking forward to working with him, and other district officials, in taking this initiative forward.